Fairness in concept

We all intuitively know what Fairness means to us — usually it becomes obvious when something feels unfair.

In everyday conversation, Fairness is usually hard to pin down. You may feel unfairly treated, but it is hard to explain to someone how they are acting unfairly. This disconnect is common and can cause problems when trying to resolve conflicts.

Many who work in the Fairness field (Ombudspersons, lawyers, administrators) find it helpful to break Fairness into distinct principles, so that it can be better communicated and examined. When the standards are clear cut, it is easier to show what is acceptable and what is not. When the concept of Fairness is transformed like this — especially when referring to a public body’s decisions — it is often called Administrative Fairness.

Administrative Fairness

Administrative Fairness focuses on decisions made by public bodies that impact people. This includes the decisions made my representatives of UVic (faculty, staff, administrators) who make decisions that impact others on campus.

Administrative Fairness generally looks at issues such as: Was a person given the opportunity to participate in a decision that impacted them? Was a decision made without bias and according to the established rules? Was a decision considerate of the person’s circumstances and based on all the information? Was the person given clear reasons why a decision was made?

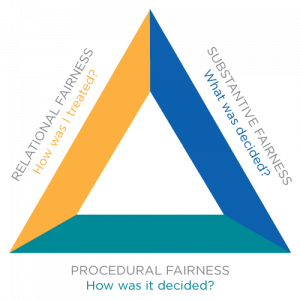

To help see if a situation was fair or not, it can be helpful to break it down to three categories:

- Procedural: Was the process leading up to the decision fair?

- Relational: Was the person treated fairly throughout the process?

- Substantive: Was the decision itself fair?

The Fairness Triangle (adapted from Ombudsman Saskatchewan) is a visual representation of the three aspects of Adminsitrative Fairness: Procedural, Relational, and Substantive.

Fairness is flexible

There are few absolutes in the field of Fairness. The more serious or the more important the decision is for the person impacted, the more Fairness is required.

For example, a 10% late penalty decision will require less fairness than a decision that results in a fail. This means that it may be acceptable to automatically apply the late penalty and be available to speak to students if they have extenuating circumstances. However, if the decision would fail the student in the course (e.g. denied concession, academic misconduct, severe late penalty), it would be more appropriate to provide more robust Fairness protections to ensure the students is given an opportunity to participate in the decision, have their views considered, and receive meaningful reasons why.

When in doubt, err on the side of caution and provide more Fairness. Fairness benefits all by fostering trust and respect and creating the conditions for robust decisions.

Consistency versus fairness

Ensuring all are subject to the same rules creates predictability and guards against arbitrary decisions. Consistent rules must be a feature of a modern administrative system where there are many decision-makers making many different decisions. Otherwise, inconsistent rules could lead to confusion, unfair treatment, and a lack of trust.

This necessity, however, can clash with our modern conceptions of equity, otherwise known as substantive equality. Equity demands that decision-makers respond to individual factors and customize outcomes. To apply the same outcome to all can ignore barriers that certain groups face and reinforce harmful social imbalances.

To lessen this tension, policies often designate an individual to assess an individual’s case and grant them the power to provide customized outcomes. Often, policy makers will use the word “normally” to indicate that a rule should not be absolute. However, in many administrative systems, these individual decision-makers are under-resourced, or lack time or knowledge to properly exercise their discretion.

The phrase: “In fairness to all students…”, when delivered by a decision-maker, can be an indicator of a failure to consider equity. Although consistency must play a factor, treating all students the same ignores both the policy language and the reality that all students are not the same.

The Fairness Tradeoff

The value of Fairness to the person impacted by a decision is obvious. Few would object to being provided the opportunity to participate in a decision that impacts them; have their case judged by an impartial party; or receive meaningful reasons why a decision was made.

For institutions and decision-makers, Fairness can be both tedious and resource-draining. Providing robust protections for each individual can be difficult to undertake, expensive, and require many decision-makers, who likely manage other responsibilities.

Despite these difficulties, the tradeoff lies in favour of providing Fairness. Consider the following:

- Fairness can avoid escalating conflicts. When a decision is made fairly, individuals, even if they disagree, are more likely to accept the outcome and not escalate further. Fewer appeals mean fewer resources and fewer dissatisfied appellants.

- Fairness is a legal requirement. Administrative law principles apply to Universities as public bodies. Providing Fairness avoids liability.

- Fairness is the ethical thing to do. Acting in a fair manner is responsible, respectful, and can go a long way to discourage feelings of disrespect, distrust, and undue stress. Acting unfairly can cause unnecessary harm — often to people in vulnerable positions.

Unfairness is not just Disagreement

Conversationally, someone may call a decision they don’t like or that they weren’t expecting unfair. When seen through the lens of administrative fairness, disagreement with the outcome does not make a decision unfair.

This disconnect is most common during appeals. Simply showing that one disagrees with a decision is not enough to be successful on appeal. Appeals are generally designed to review if a process was fair and provide relief — they are not simply a venue to have your case re-assessed.

To show that a decision was unfair, one must point to a flawed procedural step (procedural fairness), a flaw in the decision itself (substantial fairness), or disrespectful behaviour (relational fairness). Often, one needs to show how this unfairness then impacted the decision to such an extent that it should be changed. In some instances, even if something is unfair, it may not be enough to justify changing the original decision.